"Battered by Floods and Trapped in Debt, Pakistani Farmers Struggle to Survive" for The New York Times (2022)

The recent flooding has plunged small farmers in sharecropping arrangements further into debt with their landlords — a cycle that has worsened as extreme weather events become increasingly common.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/01/world/asia/pakistan-flood-farmers.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/01/world/asia/pakistan-flood-farmers.html

"A Year Under the Taliban" for The New York Times (2022)

A single year of extremist rule has turned life upside down for Afghans, especially women. Kiana Hayeri who has long called the country home captured the jarring changes.

The country they are trying to leave has changed profoundly from the one the militants took over just a year ago.The Ministry of Women’s Affairs is now the Ministry of Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice. Afghanistan’s National Institute of Music is now a Taliban base. The British Embassy has been turned into a madrasa, an Islamic theology school for young men pursuing Islamic studies.People, too, have had to redefine themselves overnight, especially the members of the old armed forces and employees of the previous government. Those who once wore uniforms or suits and rode around the city in armored vehicles now find themselves wearing traditional Afghan clothes and driving a modest car, or even pushing a vegetable cart.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/30/world/asia/afghanistan-kabul-taliban-women.html

The country they are trying to leave has changed profoundly from the one the militants took over just a year ago.The Ministry of Women’s Affairs is now the Ministry of Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice. Afghanistan’s National Institute of Music is now a Taliban base. The British Embassy has been turned into a madrasa, an Islamic theology school for young men pursuing Islamic studies.People, too, have had to redefine themselves overnight, especially the members of the old armed forces and employees of the previous government. Those who once wore uniforms or suits and rode around the city in armored vehicles now find themselves wearing traditional Afghan clothes and driving a modest car, or even pushing a vegetable cart.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/30/world/asia/afghanistan-kabul-taliban-women.html

"In Pakistan’s Record Floods, Villages Are Now Desperate Islands" for The New York Times (2022)

The flooding has affected more than 33 million people, submerging vast areas of Pakistan that are likely to take months to dry out. The devastating floods have inundated hundreds of villages across much of Pakistan’s fertile land. In Sindh Province in the south, the floodwater has effectively transformed what was once farmland into two large lakes that have engulfed entire villages and turned others into fragile islands. The flooding is the worst to hit the country in recent history, according to Pakistani officials. They warn that it may take three to six months for the floodwaters to recede.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/14/world/asia/pakistan-floods.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/14/world/asia/pakistan-floods.html

"The Bloody Uprising Against the Taliban Led by One of Their Own" for The New York Times (2022)

The rumbling of engines echoed across the valley at dusk, as scores of men with mismatched camouflage and mud-caked Kalashnikovs descended into the town in northern Afghanistan.Many had driven hours down the snow-capped mountains to reach the town and join forces with Mawlawi Mahdi Mujahid, a former Shiite commander within the mostly Sunni Taliban who had recently renounced the new Taliban government and seized control of this district.For months, the Taliban had tried to bring him back into their fold, wary of his growing clout among some Afghan Shiites eager to rebel against a movement that persecuted them for decades. Now, Taliban forces were massing around the district he controlled — and Mahdi and his men were readying to fight.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/18/world/asia/afghanistan-uprising-taliban-mahdi.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/18/world/asia/afghanistan-uprising-taliban-mahdi.html

"‘I Have Nothing Left’: Flooding Adds to Afghanistan’s Crises" for The New York Times (2022)

Widespread flash floods have left more than 40 dead and 100 others injured in recent days, battering a country already reeling from an economic crisis, terrorist attacks and other natural disasters.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/18/world/asia/afghanistan-flood-taliban.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/18/world/asia/afghanistan-flood-taliban.html

"Taliban Rewind the Clock" for The New York Times (2022)

Girls are barred from secondary schools and women from traveling any significant distance without a male relative. Men in government offices are told to grow beards, wear traditional Afghan clothes and prayer caps, and stop work for prayers.

Music is officially banned, and foreign news broadcasts, TV shows and movies have been removed from public airwaves. At checkpoints along the streets, morality police chastise women who are not covered from head to toe in all-concealing burqas and headpieces in public.

A year into Taliban rule, Afghanistan has seemed to hurtle backward in time. The country’s new rulers, triumphant after two decades of insurgency, have reinstituted an emirate governed by a strict interpretation of Islamic law and issued a flood of edicts curtailing women’s rights, institutionalizing patriarchal customs, restricting journalists and effectively erasing many vestiges of an American-led occupation and nation-building effort.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/12/world/asia/afghanistan-taliban.html

Music is officially banned, and foreign news broadcasts, TV shows and movies have been removed from public airwaves. At checkpoints along the streets, morality police chastise women who are not covered from head to toe in all-concealing burqas and headpieces in public.

A year into Taliban rule, Afghanistan has seemed to hurtle backward in time. The country’s new rulers, triumphant after two decades of insurgency, have reinstituted an emirate governed by a strict interpretation of Islamic law and issued a flood of edicts curtailing women’s rights, institutionalizing patriarchal customs, restricting journalists and effectively erasing many vestiges of an American-led occupation and nation-building effort.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/12/world/asia/afghanistan-taliban.html

"‘We Have Nothing’: Afghan Quake Survivors Despair Over Recovery" for The New York Times (2022)

With the economy in ruins and aid in short supply, survivors of the earthquake in this remote stretch of eastern Afghanistan wonder what their next move could be.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/25/world/asia/afghanistan-earthquake-recovery-aid.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/25/world/asia/afghanistan-earthquake-recovery-aid.html

"In Afghan Quake: ‘I Did Not Expect to Survive’" for The New York Times (2022)

As the earth shook, she said, speaking through her tears, she felt the walls of the room collapsing on her. Then everything went dark. When Hawa, a 30-year-old mother of six, regained consciousness, she was choking on dust, and struggled to make sense of the scene around her.“I did not expect to survive,” she said on Thursday from her hospital bed in Sharana, the provincial capital of Paktika Province in Afghanistan’s southeast.Her village, Dangal Regab, like many others in Paktika’s Geyan district, was a tableau of death and destruction in the wake of the 5.9-magnitude earthquake that struck in the early hours of Wednesday — the deadliest in Afghanistan in two decades.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/23/world/asia/afghanistan-earthquake-survivors-relief.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/23/world/asia/afghanistan-earthquake-survivors-relief.html

"To Survive, Some Afghans Sift Through Deadly Remnants of Old Wars" for The New York Times (2022)

In this once strategically important thoroughfare that connects Wardak and Logar Provinces, the Soviet war of the 1980s is buried beneath the civil war of the 1990s, which lies beneath the 20-year American war that ended in August. The rolling hills, between jagged mountains, have turned into a congealed mass of discarded steel and hidden explosives.

The valley is a scrapper’s fever dream, a place where 15 pounds of discarded metal can be quickly harvested and sold for around a dollar. But in the nine months since the Taliban took over Afghanistan, more than 180 people have been killed by unexploded munitions, many of whom were trying to collect and sell scrap, according to United Nations and Taliban officials.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/14/world/asia/afghan-scrap-metal-mines.html

The valley is a scrapper’s fever dream, a place where 15 pounds of discarded metal can be quickly harvested and sold for around a dollar. But in the nine months since the Taliban took over Afghanistan, more than 180 people have been killed by unexploded munitions, many of whom were trying to collect and sell scrap, according to United Nations and Taliban officials.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/14/world/asia/afghan-scrap-metal-mines.html

"‘Fighting Was Easier’: Taliban Take On a Treacherous, Avalanche-Prone Pass" for The New York Times (2022)

The Taliban commander’s sneakers had soaked through from the melting snow, but that was the least of his problems. It was avalanche season in the Salang Pass, a rugged cut of switchback roads that gash through the Hindu Kush mountains in northern Afghanistan like some man-made insult to nature, and he was determined to keep the essential trade route open during his first season as its caretaker.

The worry about traffic flow was both new and strange to the commander, Salahuddin Ayoubi, and his band of former insurgents. Over the last 20 years, the Taliban had mastered destroying Afghanistan’s roads and killing the people on them. Culverts, ditches, bridges, canal paths, dirt trails and highways: None were safe from the Taliban’s array of homemade explosives.

But that all ended half a year ago. After overthrowing the Western-backed government in August, the Taliban are now trying to save what’s left of the economic arteries they had spent so long tearing apart.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/03/world/asia/afghanistan-taliban-salang-pass.html

The worry about traffic flow was both new and strange to the commander, Salahuddin Ayoubi, and his band of former insurgents. Over the last 20 years, the Taliban had mastered destroying Afghanistan’s roads and killing the people on them. Culverts, ditches, bridges, canal paths, dirt trails and highways: None were safe from the Taliban’s array of homemade explosives.

But that all ended half a year ago. After overthrowing the Western-backed government in August, the Taliban are now trying to save what’s left of the economic arteries they had spent so long tearing apart.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/03/world/asia/afghanistan-taliban-salang-pass.html

"Kabul’s Sudden Fall to Taliban Ends U.S. Era in Afghanistan" for The New York Times (2021)

Taliban fighters poured into the Afghan capital on Sunday amid scenes of panic and chaos, bringing a swift and shocking close to the Afghan government and the 20-year American era in the country.

President Ashraf Ghani of Afghanistan fled the country, and a council of Afghan officials, including former President Hamid Karzai, said they would open negotiations with the Taliban over the shape of the insurgency’s takeover. By day’s end, the insurgents had all but officially sealed their control of the entire country.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/15/world/asia/afghanistan-taliban-kabul-surrender.html

President Ashraf Ghani of Afghanistan fled the country, and a council of Afghan officials, including former President Hamid Karzai, said they would open negotiations with the Taliban over the shape of the insurgency’s takeover. By day’s end, the insurgents had all but officially sealed their control of the entire country.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/15/world/asia/afghanistan-taliban-kabul-surrender.html

"In Taliban-Controlled Areas, Girls Are Fleeing for One Thing: an Education" for The New York Times (2021)

The order to shut down the girls’ schools was announced at the mosque, in a meeting with village elders. The news filtered through the teachers, in subdued meetings at students’ homes. Or came in a curt letter to the local schools’ chiefs.

Appeals to the Taliban, arguing and entreaties were useless. So three years ago, girls older than 12 stopped attending classes in the two rural districts just south of this low-slung provincial capital in Afghanistan’s northwest. Up to 6,000 girls were pushed out of school, overnight. Male teachers were abruptly fired: What they had done, provided an education to girls, was against Islam, the Taliban said.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/17/world/asia/afghanistan-taliban-girls-school.html

Appeals to the Taliban, arguing and entreaties were useless. So three years ago, girls older than 12 stopped attending classes in the two rural districts just south of this low-slung provincial capital in Afghanistan’s northwest. Up to 6,000 girls were pushed out of school, overnight. Male teachers were abruptly fired: What they had done, provided an education to girls, was against Islam, the Taliban said.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/17/world/asia/afghanistan-taliban-girls-school.html

"Why Do We Deserve to Die? Kabul's Hazaras Bury Their Daughters." for The New York Times (2021)

A bomb attack that killed scores of schoolgirls, members of a long-persecuted minority, offered still more evidence that Afghanistan may be on the verge of unraveling.

One by one they brought the girls up the steep hill, shrouded bodies covered in a ceremonial prayer cloth, the pallbearers staring into the distance. Shouted prayers for the dead broke the silence.The bodies kept coming and the gravediggers stayed busy, straining in the hot sun. The ceaseless rhythm was grim proof of the preceding day’s news: Saturday afternoon’s triple bombing at a local school had been an absolute massacre, targeting girls. There was barely room atop the steeply pitched hill for all the new graves.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/09/world/europe/afghanistan-school-attack-hazaras.html

One by one they brought the girls up the steep hill, shrouded bodies covered in a ceremonial prayer cloth, the pallbearers staring into the distance. Shouted prayers for the dead broke the silence.The bodies kept coming and the gravediggers stayed busy, straining in the hot sun. The ceaseless rhythm was grim proof of the preceding day’s news: Saturday afternoon’s triple bombing at a local school had been an absolute massacre, targeting girls. There was barely room atop the steeply pitched hill for all the new graves.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/09/world/europe/afghanistan-school-attack-hazaras.html

"Bombing Outside Afghan School Kills at Least 90, With Girls as Targets" for The New York Times (2021)

Powerful explosions outside a high school in Afghanistan’s capital on Saturday killed at least 90 people and wounded scores more, many of them teenage girls leaving class, in a gruesome attack that underscored fears about the nation’s future after the impending American troop withdrawal.The blasts — and the targeting of girls as they left the Sayed Ul-Shuhada high school — came as rights groups and others were expressing alarm that the American troop withdrawal would leave women, and their educational and social gains, particularly vulnerable.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/08/world/asia/bombing-school-afghanistan.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/08/world/asia/bombing-school-afghanistan.html

"In Afghanistan, a Booming Kidney Trade Preys on the Poor" for The New York Times (2021)

Widespread poverty and an ambitious private hospital are helping to fuel an illegal market — a portal to new misery for the country’s most vulnerable. Amid the bustle of beggars and patients outside a crowded hospital, there are sellers and buyers, casting wary eyes at one another: The poor, seeking cash for their vital organs, and the gravely ill or their surrogates, looking to buy.

The illegal kidney business is booming in the western city of Herat, fueled by sprawling slums, the surroundingland's poverty and unending war, an entrepreneurial hospital that advertises itself as the country’s first kidney transplantation center, and officials and doctors who turn a blind eye to organ trafficking.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/06/world/asia/selling-buying-kidneys-afghanistan.html

"For Women in Afghan Security Forces, a Daily Battle" for The New York Times (2020)

Even after more than a billion dollars spent on women’s empowerment projects, the daily reality for women trying to break into public roles — particularly with the government and the security forces — remains bleak. Women are still almost completely absent in high-level meetings where decisions of war, peace and politics are made. Work for women at routine jobs is a daily barrage of harassment, insult and abuse.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/20/world/asia/afghanistan-women-police.html

A new generation of Afghan women is moving to take up public and leadership roles. However, the price is a daily barrage of abuse and the fear that - even before any power-sharing with Taliban - the gains have even remained too few, too shallow and too fragile.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/20/world/asia/afghanistan-women-police.html

"There's no humanity left" for The Washington Post (2020)

Hajar Sarwari was in labor with her second child at a west Kabul maternity ward on Tuesday morning when gunmen shot her twice in the abdomen, killing her and her unborn child. Her family buried her atop a hill under overcast skies on the outskirts of the Afghan capital Wednesday morning, one day after three gunmen killed 24 people in a Doctors Without Borders maternity ward. The baby remained in her womb.

Her mother wept uncontrollably, supported by a group of women in long black robes. Outside, her 6-year-old daughter Razia played and giggled in the courtyard.

No one had told her what had happened to her mother.

Rahila, her aunt, said the young girl had been eager to go to the hospital with her mother. “I told her, ‘Don’t go, wait here. Mommy will bring a baby for you,’ ” she recalled and then began to cry.

“I don’t know how to tell her that her mommy is dead,” she said.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/afghanistan-maternity-ward-attack-kabul-babies-mothers/2020/05/13/d997ae38-9526-11ea-87a3-22d324235636_story.html

"In Kabul's Heart, Soviet Towers Harbor Decades of Tales", For The New York Times (2020)

The scars from four decades of war are etched into the boxy apartment towers known as Macroyan Kohna, a dreary neighborhood built by the Soviets in central Kabul a half-century ago as a testament to modernity.

Like other parts of the Afghan capital, Macroyan Kohna has been pummeled by rockets, mortar shells and car bombs since the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan began just over 40 years ago. But the leafy neighborhood of shrapnel-pocked apartments has been rebuilt and expanded several times over.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/09/world/asia/kabul-afghanistan-soviet-housing.html

Like other parts of the Afghan capital, Macroyan Kohna has been pummeled by rockets, mortar shells and car bombs since the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan began just over 40 years ago. But the leafy neighborhood of shrapnel-pocked apartments has been rebuilt and expanded several times over.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/09/world/asia/kabul-afghanistan-soviet-housing.html

"Scarred and Weary, an Afghan Force Wonders: What Is Peace?" for The New York Times (2020)

Their young bodies are as broken as the bomb-pocked 40 miles of highway they guard.

Some are missing fingers, others a leg or an eye. Many carry multiple scars and the ringing sound of the last explosion trapped in their heads. Most have not been home in years — to go home is to drive into Taliban territory. So their mothers come to them once in a while, with dried fruit or embroidered tunics.

A brief truce has brought this battle-weary unit of the Afghan police, holed up in their hilltop outposts in Zabul Province, an unexpected respite from the daily attacks they had come to see as inevitable. In the final days before a peace deal between the United States and the Taliban insurgency was expected to be signed, and the partial cease-fire that was set as a precondition seems to be holding. The police on this remote, southern battlefield suddenly have time for questions they once hardly imagined asking: Could there really be peace? What would that be like?

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/27/world/asia/afghanistan-taliban-peace.html

Some are missing fingers, others a leg or an eye. Many carry multiple scars and the ringing sound of the last explosion trapped in their heads. Most have not been home in years — to go home is to drive into Taliban territory. So their mothers come to them once in a while, with dried fruit or embroidered tunics.

A brief truce has brought this battle-weary unit of the Afghan police, holed up in their hilltop outposts in Zabul Province, an unexpected respite from the daily attacks they had come to see as inevitable. In the final days before a peace deal between the United States and the Taliban insurgency was expected to be signed, and the partial cease-fire that was set as a precondition seems to be holding. The police on this remote, southern battlefield suddenly have time for questions they once hardly imagined asking: Could there really be peace? What would that be like?

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/27/world/asia/afghanistan-taliban-peace.html

"It Is Just Me and the Water" for The New York Times (2019)

When Fatema Saeedi is in the pool, she cannot hear the crowded, chaotic noise of the city around her. She does not think about suicide bombings or Taliban attacks. She concentrates on her breathing as she moves through the water. One hand in front of the other. Exhale.

For Ms. Saeedi, 26, the swimming pool is a refuge. The clean water, the walls and the women around her — all sealed off from the male patrons nearby — are a welcome respite from Kabul, Afghanistan’s capital.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/22/world/asia/afghanistan-kabul-women-swimming.html

For Ms. Saeedi, 26, the swimming pool is a refuge. The clean water, the walls and the women around her — all sealed off from the male patrons nearby — are a welcome respite from Kabul, Afghanistan’s capital.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/22/world/asia/afghanistan-kabul-women-swimming.html

"In a Quiet Corner, An Old Afghan Poet Polishes the Heart's Mirror" for The New York Times (2019)

For more than 50 years, Haidari Wujodi’s desk in a Kabul library has been a stop for those seeking escape from the violence outside. In his quiet corner, Wujudi polishes ‘the Heart’s Mirror.’ 80-year-old Wujudi, a mystic poet, has kept a quiet window desk at the Kabul Public Library. His seat overlooks the hustle and bustle of the Afghan capital city, all but unrecognizable from the day he arrived as a young library clerk — one with a dreamy mind and stammering speech, but fine calligraphic handwriting that helped land him his day job. As governments toppled around him, Afghanistan sank deeper into flames of war that still burn. But Haidari Wujodi maintained his daily routine, switching his shoes for comfortable sandals that he wears with socks as he arrives at his desk behind stacks of fraying periodicals. His flask of tea fills and empties. About 15 men and women, members of a group called “The Society of Lovers of Mawlana,” arrive and quietly take their seats. Mr. Wujodi looks out of the window as the room fills with the warm afternoon sun and a peaceful silence. One of the members, a middle-aged man with a narrow beard and a beautiful melodic voice, sings several verses as the rest follow along in their copies of the book. Then, in a soft but shaky voice, his head trembling, Mr. Wujodi begins explaining the verses.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/25/world/asia/afghanistan-poet-haidari-wujodi.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/25/world/asia/afghanistan-poet-haidari-wujodi.html

"Bombed by ISIS, an Afghan Wrestling Club Is Back: ‘They Can’t Stop Us’ "for The New York Times (2019)

The Maiwand wrestlers are back, with a vengeance. Last September, the Islamic State bombed their gym and killed dozens of them. Many of the 91 people wounded have lifelong, disabling injuries, missing limbs and worse. Five are still in critical condition. This year they have rebuilt it, and their vengeance has been to make it bigger, better and even busier than it was before and they succeeded.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/20/world/asia/afghanistan-wrestling-club-bombing.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/20/world/asia/afghanistan-wrestling-club-bombing.html

"The Money Changer of Kabul, His Daughter and Her Kidnappers" for The New York Times (2019)

Murtaza Ahmadi was one of those Afghans who somehow never seemed to suffer from the long war.No one in his family perished on the front lines with the army or the police, or disappeared for years with the Taliban only to come back in a plywood coffin. No one close to him had the bad luck to be where a bomb went off or to get caught in crossfire, relatives said.Mr. Ahmadi’s luck suddenly ran out in March. No bomb or gun was involved, but he was targeted nonetheless — for the bundles of cash he handled in his job every day, and for the 6-year-old daughter more precious to him than any of that.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/12/world/asia/afghanistan-kidnapping-ransom.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/12/world/asia/afghanistan-kidnapping-ransom.html

"Afghan Saffron" for The New York Times (2019)

Our profile of a sweet agriculture worker whose waking-hours, for more than 20 years, have been spent immersed in saffron, strategizing Afghanistan's growth as currently the world's No.3 producer of the spice.

Even his dreams have been infiltrated by it.“I once dreamed that all my wishes had been achieved,” he said, “that we were producing 50 percent of the world’s saffron and all those things. And what was I going to do now?”

“All of a sudden, that shook me awake,” he said, laughing.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/26/world/asia/afghanistan-saffron.html

Even his dreams have been infiltrated by it.“I once dreamed that all my wishes had been achieved,” he said, “that we were producing 50 percent of the world’s saffron and all those things. And what was I going to do now?”

“All of a sudden, that shook me awake,” he said, laughing.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/26/world/asia/afghanistan-saffron.html

"A Generation of Widows, Raising Children Who Will Be Forged by Loss" for The New York Times (2018)

The war in Afghanistan is disproportionately killing young men, and it is leaving behind a generation defined by that loss. Children like Benyamin will have only early memories of their fathers, and the deaths will shape their lives even as true recollections fade. Babies like Sarfarz will have even less, with death taking fathers they will never know.

Carrying it all are the tens of thousands of widows the war has created since 2001. Like Mrs. Kakar, they are left to raise families in a country with a dearth of economic opportunity and plagued by a war that kills 50 people a day.

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/01/world/asia/afghanistan-widows-war.html

Carrying it all are the tens of thousands of widows the war has created since 2001. Like Mrs. Kakar, they are left to raise families in a country with a dearth of economic opportunity and plagued by a war that kills 50 people a day.

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/01/world/asia/afghanistan-widows-war.html

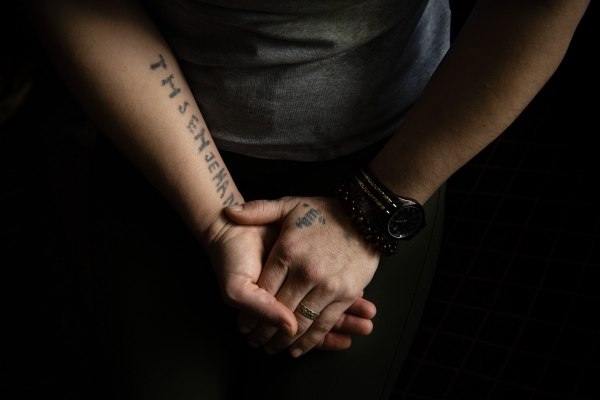

"Yazidi Sisters" for The Globe and Mail (2018)

Years after escaping her Islamic State captors, Jihan Khudher isn’t just haunted by her experiences of rape and violence – they’re making her black out. Now safe in Canada, she’s finding that refuge alone might not be enough.

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-for-a-yazidi-refugee-in-canada-the-trauma-of-isis-triggers-rare/

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-for-a-yazidi-refugee-in-canada-the-trauma-of-isis-triggers-rare/

"Along a Road of Sorrow, a Toddler Lost Her Name, Her Family and Her Life" for The New York Times (2018)

On the small whiteboard above the little girl’s hospital bed, in the medical bills that she had no one left to pay, and in the news reports about a shattered toddler’s struggle to survive, she was called Fereshta — the Persian word for angel. No one knew her real name. A shepherd had carried the child, around 2 years old, to a hospital in Kabul in October. Most of her limbs were broken and her skull was fractured by a roadside bomb in eastern Afghanistan, a blast that had wiped out most of her family. Their vehicle struck a roadside bomb in the district of Achin, the stubborn center of the Islamic State’s small presence in Afghanistan. Despite a month of treatment, she never emerged from a coma and the skull fracture proved fatal. On December 1st, 2018, she was pronounced dead. Only when her little body — shrouded in white from head to toe — made its final journey back to her hometown in Nangarhar Province, and only after the villagers there crosschecked a list of all her dead brothers and sisters, did her real name become known: Sima. We followed part of her journey home, where she rested in peace next to her little brothers and sisters in a cemetery in Achin District, along the road that had taken their lives.

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/28/world/asia/afghanistan-fereshta-sima.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/28/world/asia/afghanistan-fereshta-sima.html

"Tehran, No Longer An Island" for Wall Street Journal (2017)

Iran’s capital was hit by an unprecedented terror attack on June 7, with gunmen and suicide bombers targeting two pillars of the country’s ruling system—the parliament building and the shrine to the Islamic Republic’s founding figure, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Islamic State took responsibility—their first successful attack inside the Persian Gulf country. Seventeen people were killed:

https://graphics.wsj.com/glider/iran-b6765bbc-9cb6-488e-b368-7b5d791acabd

https://graphics.wsj.com/glider/iran-b6765bbc-9cb6-488e-b368-7b5d791acabd

"Forgotten Sherpas" for CNN (2015)

An earthquake with a 7.8 magnitude rocked Nepal on April 25th2015, leaving more than 8,500 people dead. Just over two weeks after this mammoth earthquake, the nation got hit hard again by another powerful tremor, 7.3 magnitude, that left dozens more dead and more than thousand injured.

In the aftermath of this disaster, commissioned by CNN, we made a trip to Khumjung and Namche to trek our way down to Lukla and tell the stories of Forgotten Sherpas. Sherpas are the ethnic minorities who inhabit the towns and villages in the shadow of Mount Everest and are known worldwide as expert climbers. They prop up Nepal's lucrative trekking and tourism business, yet the government has never looks out for them. A week after the first earthquake hit, we found no presence of Nepalese government nor any of the hordes of international aid workers and members of the media who descended on Kathmandu within days of the earthquake. Isolated in remote mountainous villages, they have been forgotten people in Nepal and now, after the earthquake, many of them fear being forgotten again.

https://edition.cnn.com/2015/05/08/world/nepal-forgotten-sherpas-remote-village-everest/index.html

In the aftermath of this disaster, commissioned by CNN, we made a trip to Khumjung and Namche to trek our way down to Lukla and tell the stories of Forgotten Sherpas. Sherpas are the ethnic minorities who inhabit the towns and villages in the shadow of Mount Everest and are known worldwide as expert climbers. They prop up Nepal's lucrative trekking and tourism business, yet the government has never looks out for them. A week after the first earthquake hit, we found no presence of Nepalese government nor any of the hordes of international aid workers and members of the media who descended on Kathmandu within days of the earthquake. Isolated in remote mountainous villages, they have been forgotten people in Nepal and now, after the earthquake, many of them fear being forgotten again.

https://edition.cnn.com/2015/05/08/world/nepal-forgotten-sherpas-remote-village-everest/index.html

"World Cup in Tehran" for Aljazeera America (2014)

In 1998, when Iran qualified for the World Cup by winning against Australia for the first time since the islamic revolution, millions poured into the streets to express their joy, both at the prospect of being included in the World Cup and, more symbolically, at the country’s return into the global fold after years of isolation.

Iranians were captured during two breathtaking final games for Iran in 2014 World Cup, one against Nigeria and the other against Argentina. People came together in cafes, restaurants or behind the closed doors at home to watch the games with their friends, families and collegues and public celebration took on the streets when young people flooded onto major streets to carry on their festivities, buoyed by Team Melli's, the Iranian national soccer team, strong showing against top-ranked Argentina.

Iranians were captured during two breathtaking final games for Iran in 2014 World Cup, one against Nigeria and the other against Argentina. People came together in cafes, restaurants or behind the closed doors at home to watch the games with their friends, families and collegues and public celebration took on the streets when young people flooded onto major streets to carry on their festivities, buoyed by Team Melli's, the Iranian national soccer team, strong showing against top-ranked Argentina.